European institutions and the EU anti-discrimination policy

| Sito: | Moodle OBC - Transeuropa |

| Corso: | The Parliament of Rights |

| Libro: | European institutions and the EU anti-discrimination policy |

| Stampato da: | Utente ospite |

| Data: | martedì, 10 marzo 2026, 02:58 |

1. Introduction

The European Union is a supranational organisation that brings together 27 European countries in a consortium of liberal democracies. It plays a central role in combating discrimination in Europe, also thanks to the European Parliament (EP).

Source: European Union

Discover the profiles of the 27 member states.

Before going into the details of the anti-discrimination policies used as a case study in this course, we will provide a brief overview of the EU institutions and policies, as European legislation has had a great impact in promoting and strengthening anti-discrimination legislation in member states.

2. ABC of EU Institutions

What does the European Parliament do and what are the responsibilities of the Commission? What do we mean by the European Council and how does it differ from the Council of the European Union?

|

Food for thought This video was made in 2014. Since then, the EU has undergone major changes that have also affected the information presented. Can you identify which of the information given in the video is no longer correct? |

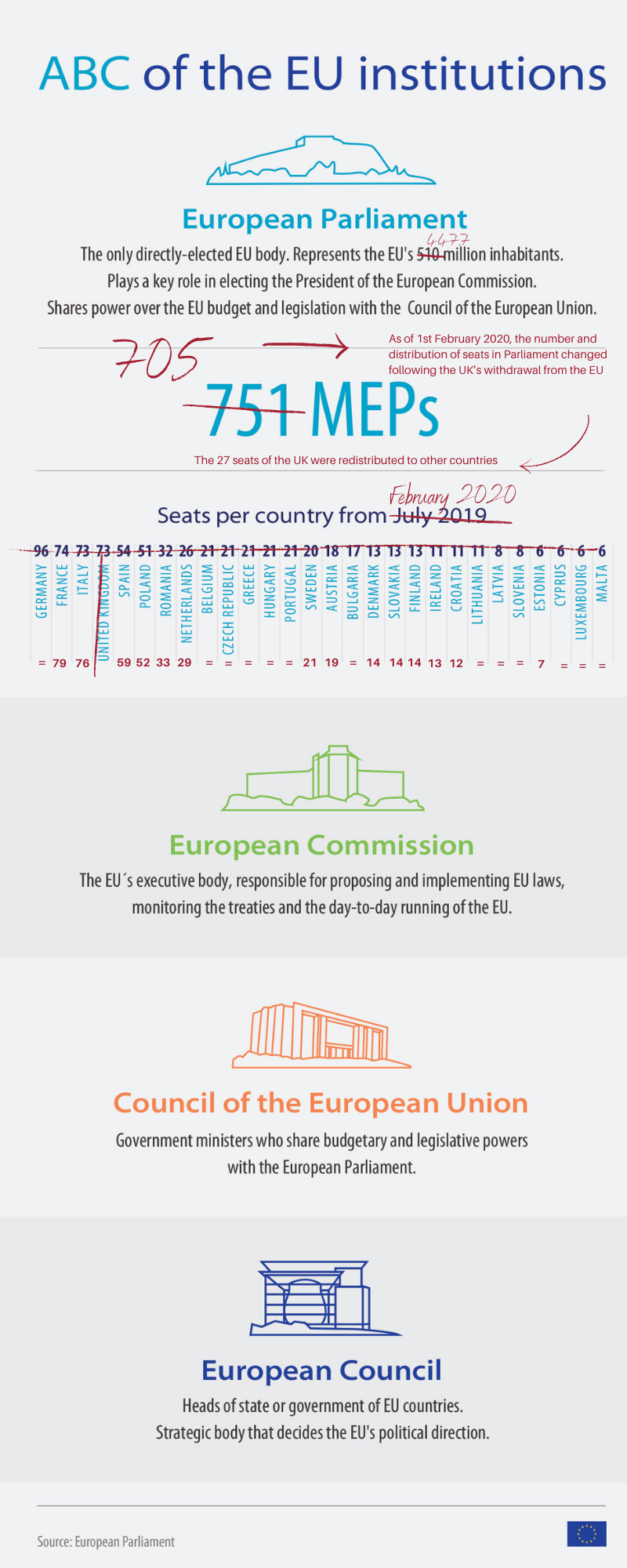

Read the infographic for a brief guide to the EU's institutions:

Source: European Union

Find out how European citizens determine the composition of the EU institutions:

Source: Multimedia Centre, European Parliament 2021

3. The division of competences between the EU and the member countries

To approach European policies and understand the role of the European Parliament, we must start from the fact that the European Union can only act within the limits of the powers that the member countries have conferred on it to achieve the common objectives defined in the treaties.

Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union (TEU): “The limits of Union competences are governed by the principle of conferral. (...) Under the principle of conferral, the Union shall act only within the limits of the competences conferred upon it by the Member States in the Treaties to attain the objectives set out therein. Competences not conferred upon the Union in the Treaties remain with the Member States”.

Source: Areas of EU action, European Commission

This video briefly presents the powers of the EU:

SPECIAL COMPETENCES

In addition to the competences described above, the Union can take measures to ensure that EU countries coordinate their economic, social, and employment policies at EU level.

In the framework of EU economic governance, for example, in 2010 the European Semester was established, a coordination period (from January to June of each year) during which member countries develop their own economic, budgetary, and employment policies in line with the indications and standards provided by the EU. Initially introduced as a coordination tool at the level of economic and budgetary policies, the European Pillar of Social Rights has been integrated in the European Semester since 2017, and later with the adoption of the European Green Deal in 2019, the sustainable development goals of United Nations 2030 Agenda. In 2020 and 2021 the European Semester underwent some temporary changes to make space for the preparation, adoption, and implementation of the Recovery and Resilience Facility introduced to face the Covid-19 pandemic.

In the sectors in which the EU does not have legislative powers but only supportive powers, because these are those areas in which the States do not want to lose sovereignty and/ or in which the harmonisation of legislation is particularly difficult given the variety of political-institutional contexts, the coordination of national policies is also implemented through another instrument, the Open Method of Coordination (OMC): the Member States, while not introducing legally binding common regulations, nevertheless try to coordinate themselves, to set joint objectives, to discuss, share good practices, and monitor each other. This is particularly the case in the fields of employment, social protection, education, youth, and vocational training.

The EU's common foreign and security policy is characterised by specific institutional aspects, such as the limited participation of the European Parliament and the European Commission in the decision-making process and the exclusion of any legislative activity. This policy is defined and implemented by the European Council (made up of the heads of state and government of the EU countries) and by the Council of the European Union (made up of representatives of each EU country at ministerial level). The President of the European Council and the High Representative of the Union for Foreign and Security Policy represent the EU in matters of common foreign and security policy.

USE OF COMPETENCES

The exercise of EU competences is subject to two fundamental principles established in Article 5 of the Treaty on European Union:

principle of subsidiarity : in the area of its non-exclusive competences, the EU can only act if, and to the extent that, the objective of a proposed action cannot be satisfactorily achieved by EU countries, but it could be better achieved at community level;

principle of proportionality: the content and scope of EU action cannot exceed what is necessary for the achievement of the objectives of the treaties.

Article 5 of the TEU:

“The use of Union competences is governed by the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality.(...) Under the principle of subsidiarity, in areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Union shall act only if and in so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, either at central level or at regional and local level, but can rather, by reason of the scale or effects of the proposed action, be better achieved at Union level. The institutions of the Union shall apply the principle of subsidiarity as laid down in the Protocol on the application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality. National Parliaments ensure compliance with the principle of subsidiarity in accordance with the procedure set out in that Protocol.

Under the principle of proportionality, the content and form of Union action shall not exceed what is necessary to achieve the objectives of the Treaties. The institutions of the Union shall apply the principle of proportionality as laid down in the Protocol on the application of the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality".

4. European Legislation

The complex legal structure of the European Union has evolved over time. It is worth summing up its trajectory and the repercussions it has had on the development of anti-discrimination laws (source FRA 2018).

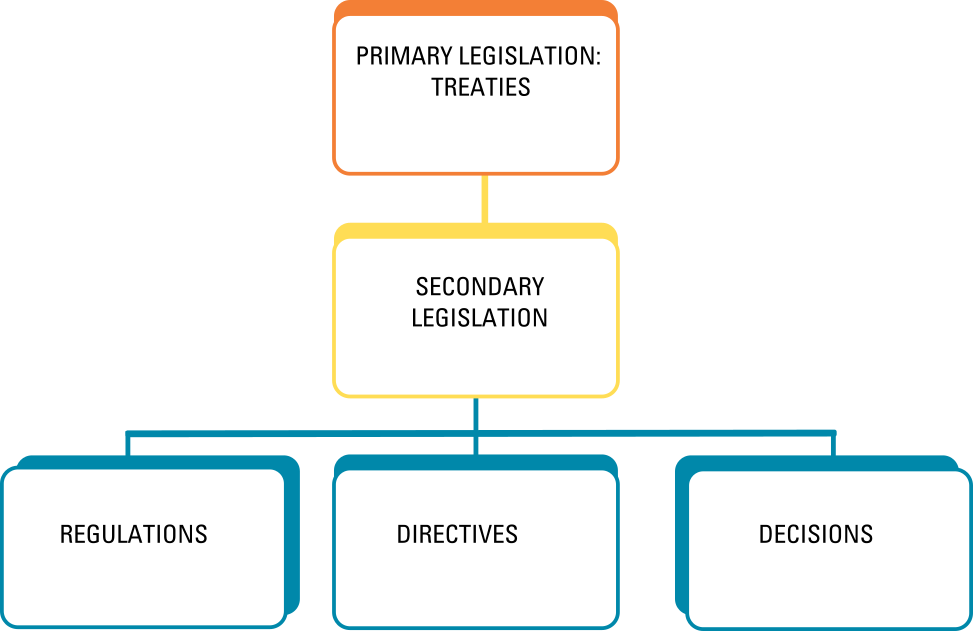

European Union law is part of the legal system of each Member State. It is divided into primary law and secondary law. Primary law establishes the division of competences between the European Union and the member states and defines the legal framework within which the EU institutions implement policies.

Secondary law includes:

regulations: of general application, binding in all their elements and directly applicable in all European Union countries, without the need for transposition into national law. They must be fully respected by the recipients: individuals, member states, and Union institutions;

directives: they bind the member states with regard to a common objective to be achieved, while leaving the national authorities with the power to decide on the form and means by which to achieve the objectives set. The directive must be implemented by the member state through a specific law that adapts the national legislation to the objectives indicated;

decisions: they are binding in all elements but only towards the recipients, for example a member country, individuals, a company, etc.

In addition to these binding legal acts, there are also non-binding legal acts or recommendations and opinions (Article 288 of the TFEU).

The jurisprudence of the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) also constitutes a source of Community law.

5. The legislative process

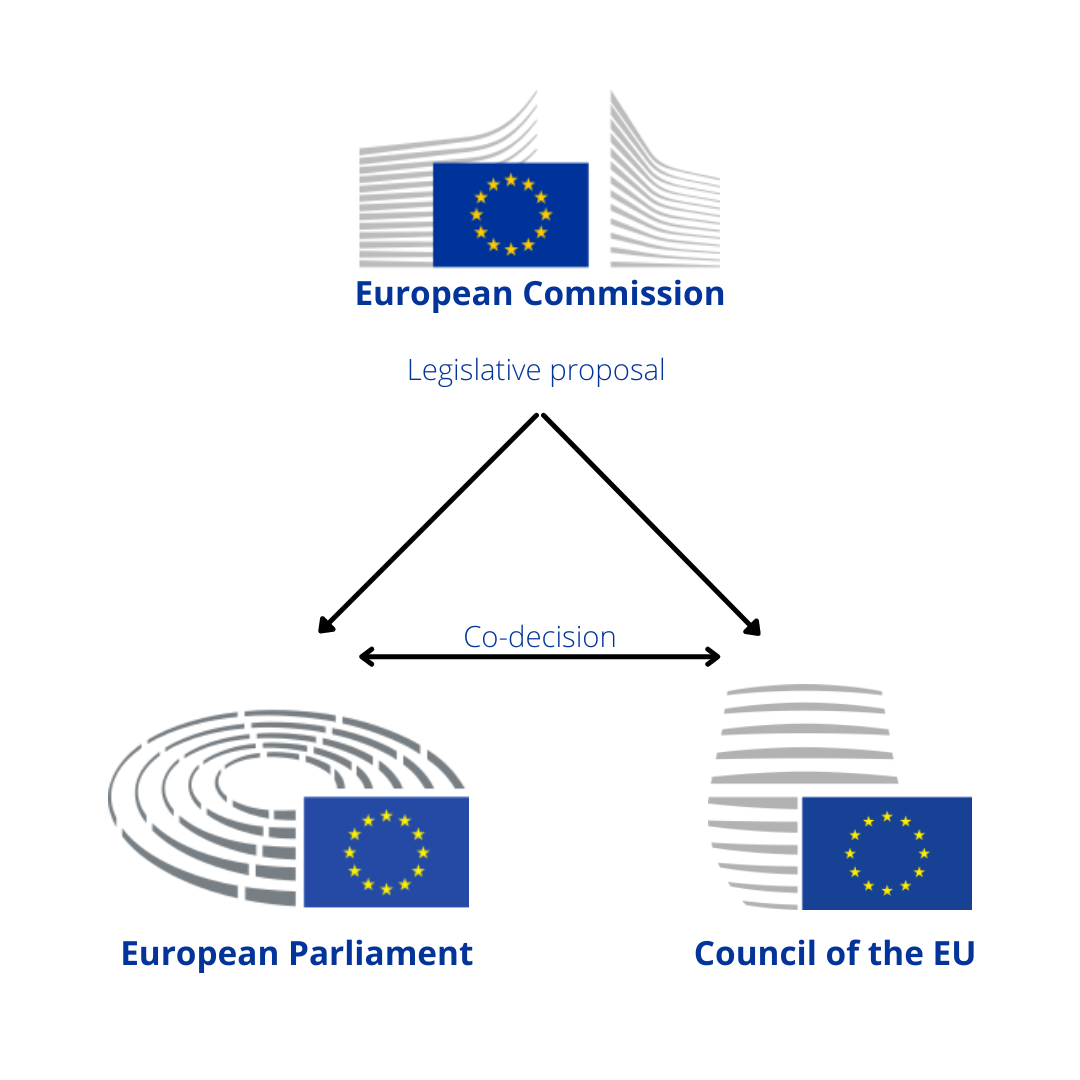

The EU legislative process develops within the so-called "institutional triangle" made up of three EU institutions:

EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT

The European Parliament, the only directly elected body of the EU, represents the over 447 million inhabitants of the member countries (data 2020, source Eurostat) and is made up of 705 deputies. It was first elected by universal suffrage in 1979. Its powers have been extended through successive amendments to the EU treaties. Its role in the legislative process is that of co-legislator together with the Council of the EU, that is, it amends and adopts the proposals of the Commission, which alone has the right of legislative initiative.

EUROPEAN COMMISSION

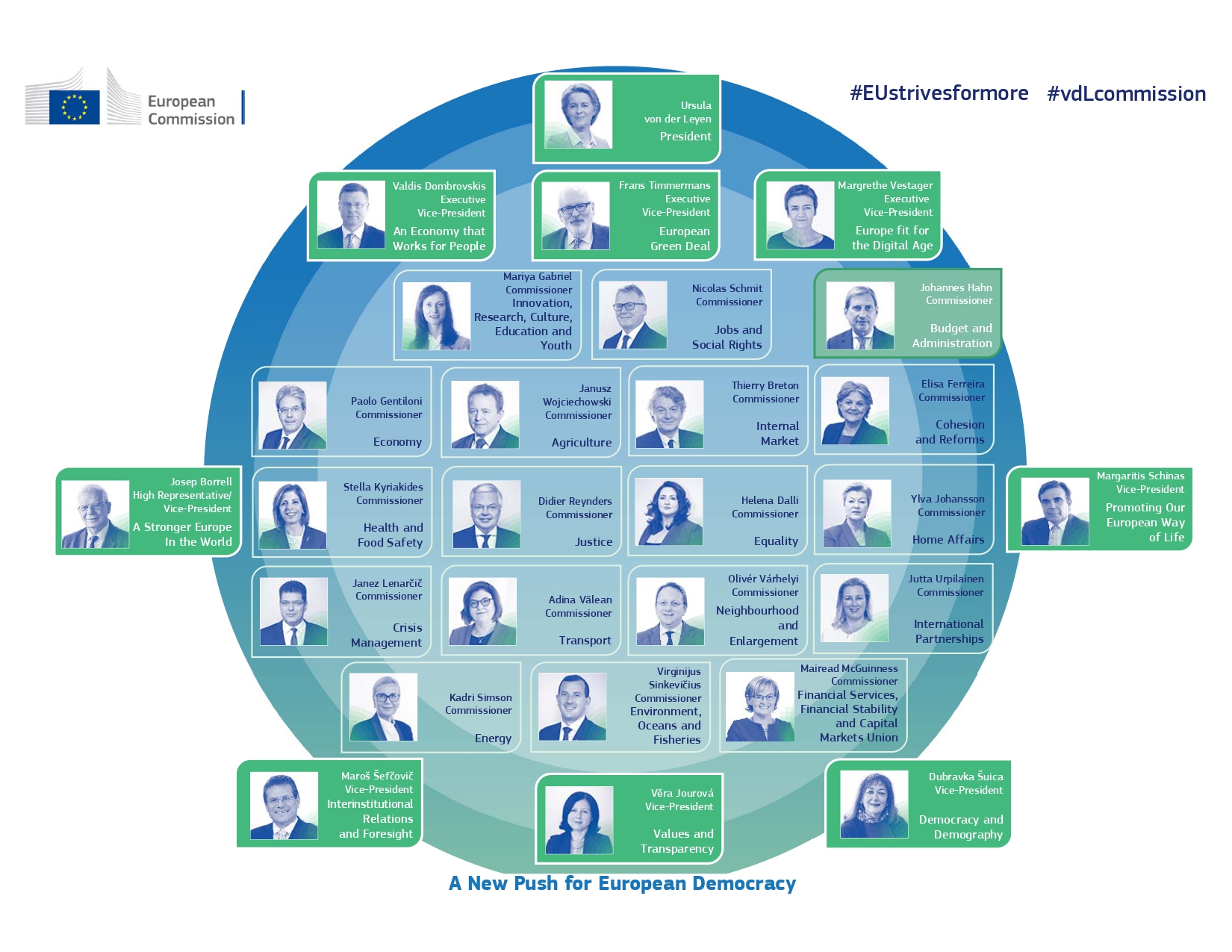

The European Commission represents the interests of the European Union as a whole. Its main functions are: to propose common policies and legislation and ensure compliance with them, ensure the implementation of policies, and manage the community budget. It is appointed every five years, following the European elections. The Commission is made up of a college of 27 commissioners (one for each member country) and led by a President elected by the Parliament on a proposal from the European Council. The commissioners are chosen by the President; once approved by Parliament, they are appointed by the European Council and officially take on their functions.

The Commission prepares legislative proposals on its own initiative, at the request of Parliament or member countries, or following citizens' initiatives, often after public consultations open to various stakeholders including civil society.

The Commission's department dealing with anti-discrimination laws is the Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion (DG EMPL).

In this infographic, the current composition of the European Commission:

Source: European Commission

Learn more about the 6 priorities of the European Commission for the period 2019-2024

THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION

The Council of the European Union represents the governments of the 27 EU member countries at ministerial level: its members are the ministers of each country responsible for the matter under discussion ( →The 10 Council formations).

The Council is chaired alternately by a member state for a period of six months. In the European decision-making process, the Council is a co-legislator together with the Parliament. Several times a month the competent ministers of each member country meet to decide on specific issues: economic affairs, transport, energy, agriculture, etc. Depending on the area, the Council decides by simple majority, by qualified majority, or by unanimity. The latter is required above all for all areas considered particularly sensitive by member countries, for example issues related to common foreign and security policy, including the accession of a new country, European finances, and issues related to social security.Qualified majority

About 80% of the deliberations of the Council of the EU take place according to the rule of "double majority" or qualified majority. According to Article 238 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) "by qualified majority we mean at least 55% of the members of the Council representing the participating Member States that total at least 65% of the population of these States”.

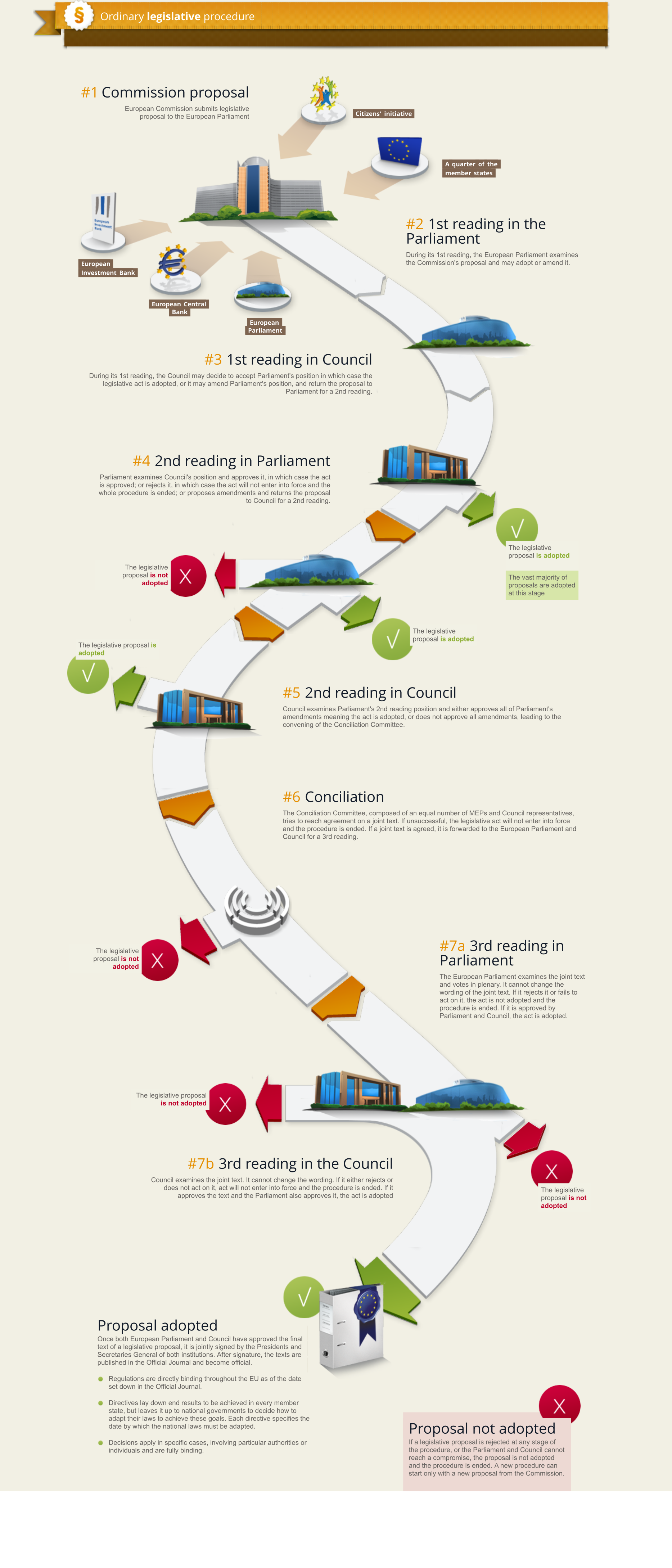

Most of the EU legislation is adopted jointly by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU using the ordinary legislative procedure, also known as codecision (COD).

Explore the infographic describing the mechanism and the possibility of one, two, or three readings by the two co-legislators and a conciliation procedure between the EP and the Council:

Source: European Parliament

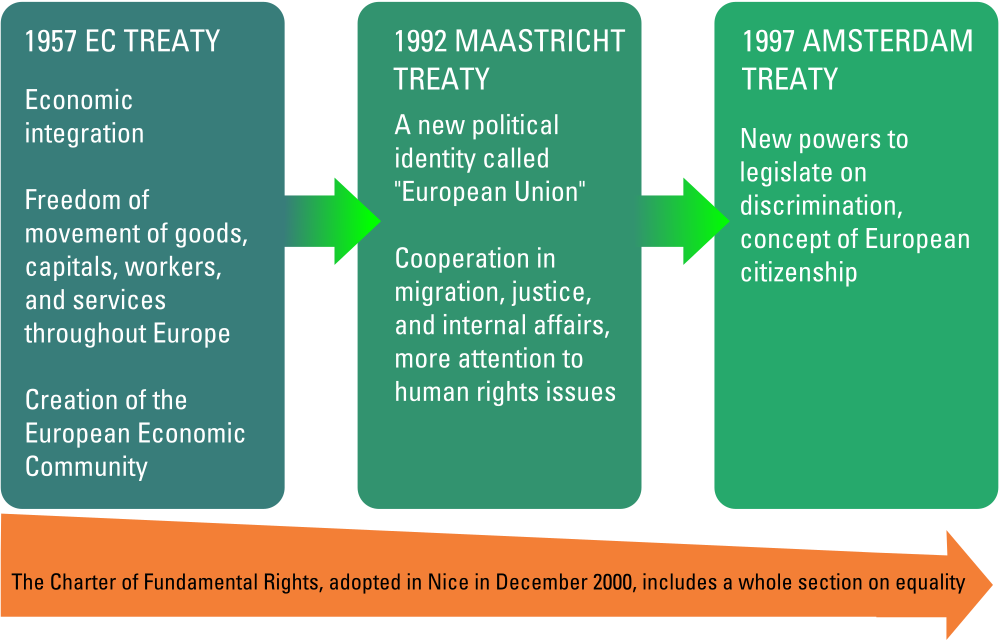

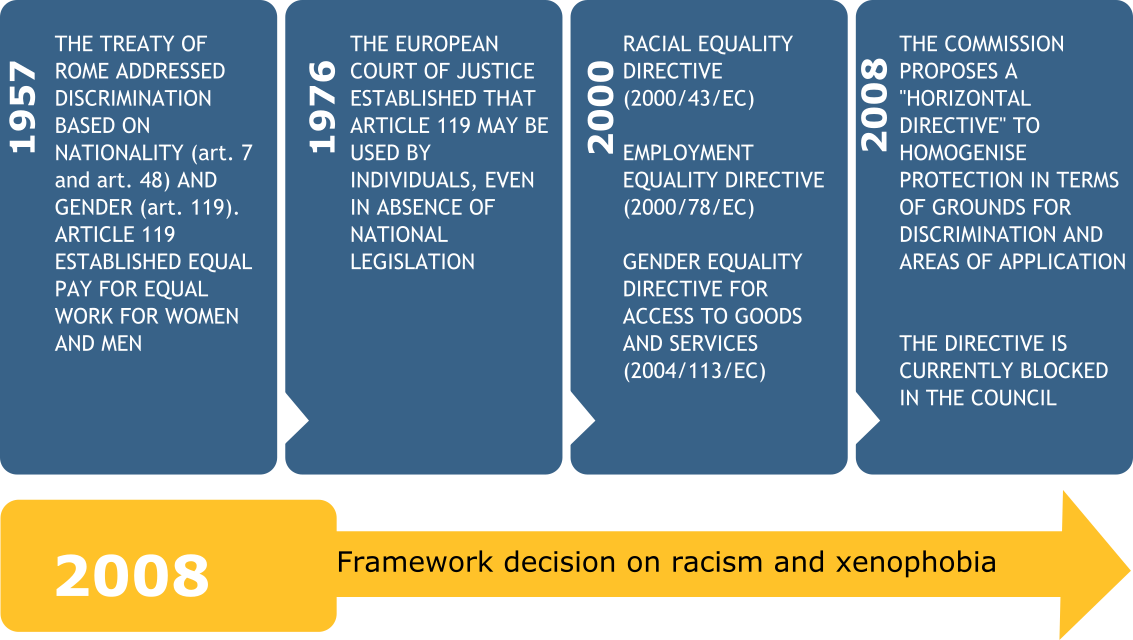

6. Early development of anti-discrimination law

The principle of non-discrimination of workers on the basis of nationality and gender had already been introduced in the 1957 Treaties of Rome in order to promote freedom of movement, equal pay, and other conditions. The Defrenne judgement, issued by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) in 1976, confirmed that equal pay is part of the fundamental principles of the Community and can therefore be invoked by European citizens even in Member States where the legislation does not provide about it.

If the first developments of anti-discrimination are linked to the needs of economic integration, there was a step forward thanks to political integration with the transformation of the European Economic Community (EEC) into the European Union starting from 1992.

The Treaty of Amsterdam of 1997 gave the EU new powers in the field of combating discrimination (Article 13) and within a few years there was a strong expansion of the legislation.

Non-discrimination also became a fundamental right in the Nice Treaty of 2000 with the adoption of the Charter of Fundamental Rights which contains a section dedicated to equality. The Charter became legally binding in the EU with the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in December 2009, acquiring the same legal effect as the EU treaties.

7. Anti-discrimination norms

In the 1990s various interest groups lobbied for the prohibition of discrimination enshrined in EU law to be extended to other areas such as: race and ethnic origin, sexual orientation, religious beliefs, age, and disability.

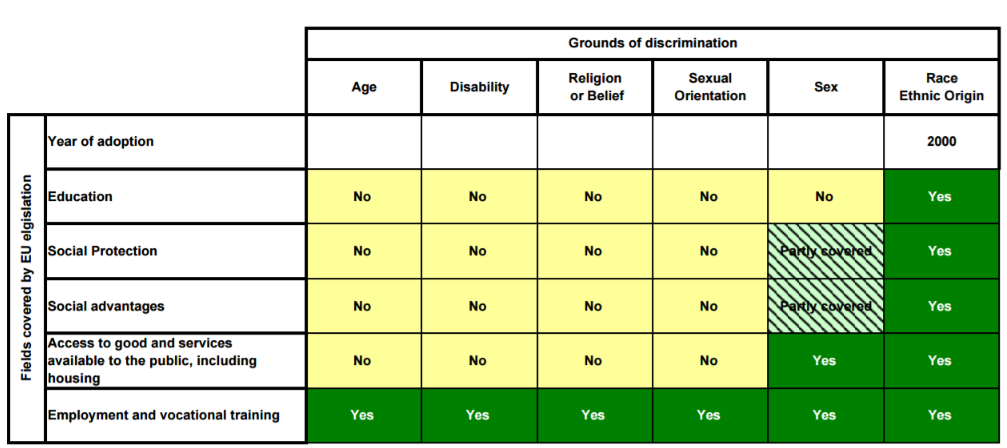

The first anti-discrimination directive introduced in European legislation was the Racial Equality Directive (2000/43/EC) which introduced the principle of equal treatment between people regardless of race or ethnic origin in the field of employment, but also in access to goods and services and in access to social protection (healthcare, education, and housing).

Shortly after, the Employment Equality Directive or Framework Employment Directive (2000/78/EC) was adopted which included the prohibition of discrimination on the basis of religion, disability , age, and sexual orientation in the workplace.

In 2004 the Gender Goods and Services Directive (2004/113/EC) extended the protection against discrimination based on sex to this sector. However, the protection against this type of discrimination does not match exactly that recognised by the Racial Equality Directive, as it guarantees equal treatment only for access to goods and services but not in the field of social protection.

Furthermore, the three anti-discrimination directives did not oblige Member States to use the criminal code to sanction discriminatory acts. That is why in 2008 an EU Council Framework Decision was introduced which obliged all EU Member States to provide for criminal sanctions in the case of inciting violence or hatred on the basis of race, skin colour, origin, religion or creed, ethnicity, and nationality as well as the dissemination of racist or xenophobic material and the excuse, denial, or trivialisation of genocide, war crimes, and crimes against humanity against these groups. Member States were also forced to consider racist or xenophobic intent as aggravating.

The summary table presented in 2012 by Social Platform in a hearing in the European Parliament shows the areas covered by European legislation:

Source: Pierre Baussand, Social Platform 2012

Since European legislation has ended up ensuring uneven protection against discrimination, the European Commission has proposed a new "horizontal directive" to standardise the guarantees provided for by the law both with respect to the grounds for discrimination and the areas of application.

The European Parliament gave its broadly positive opinion on the directive in a resolution adopted on 2 April 2009. However, the horizontal directive has been blocked in the Council since then due to opposition from seven member countries, including Germany.

Indeed, the Lisbon Treaty introduced a horizontal clause to ensure that the fight against discrimination is integrated into all EU policies and actions (Art.10 of the TFEU). For this reason, the ordinary legislative procedure (COD) with qualified majority approval is no longer enough to make regulatory changes. A special legislative procedure (APP) must be used: the Council acts unanimously, after obtaining the consent of the European Parliament.

In the Commission's programmes of 2016 and 2019, the Anti-Discrimination Directive was back in the list of EU priorities, but the necessary unanimity for its approval has not been reached yet.

8. Transposition and implementation status

The goal of anti-discrimination law is to ensure that everyone has equal and fair access to available opportunities. Persons in similar situations must be able to receive similar treatment and less favourable treatment due to some characteristic possessed is explicitly prohibited.

European citizens can exercise their right of appeal in the event of discrimination both direct - or in the case of different treatment in a comparable context - and indirect, or due to a disadvantage that cannot be justified by a legitimate and proportionate objective.

In other words, direct discrimination occurs when a person is treated worse than another person in the same situation would be treated, due to their ethnicity, sexual orientation, belief, etc. In cases of indirect discrimination, on the other hand, a person ends up being penalised by apparently neutral provisions, criteria, or behaviours, but which are disproportionate or do not have an objective justification.

All Member States have transposed anti-discrimination laws and, to date (April 2022), there are no pending infringement procedures on the transposition or application of the Employment Equality Directive. The Commission, by virtue of its obligations under the Treaties, through the infringement procedure can take action against a member state if it identifies possible violations of EU law on the basis of its own investigations or complaints from citizens, businesses, and other stakeholders. The infringement procedure may involve the EC referring the case to the Court of Justice and the imposition of financial penalties.

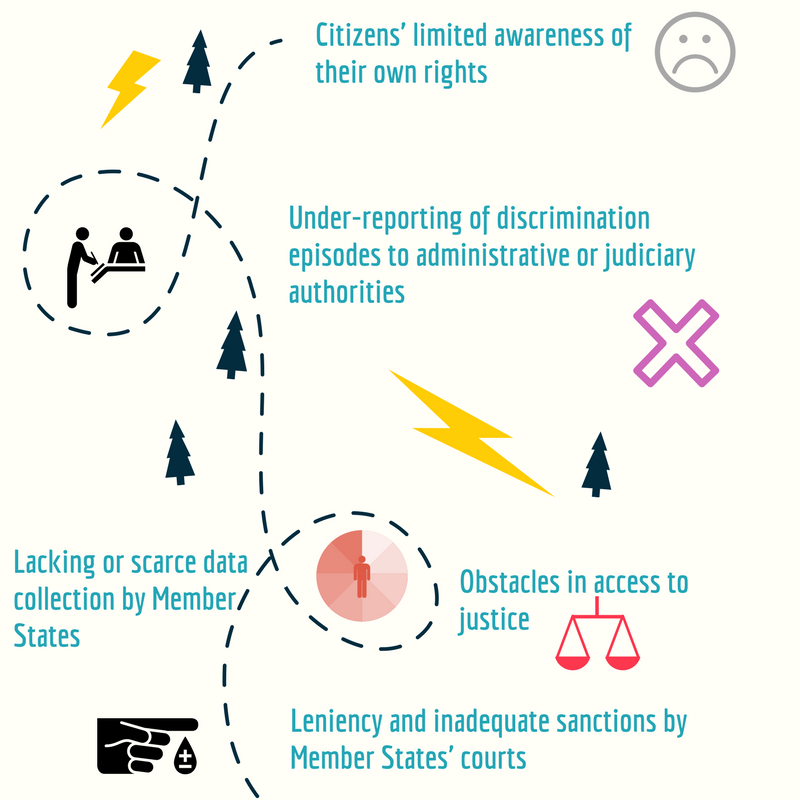

In terms of implementation, however, there are obstacles such as:

In a plenary session in October 2019, the European Parliament reiterated the need for the adoption of a directive on the new EU strategy on gender equality. During the discussion, some MEPs, while underlining the importance of the fight against discrimination, questioned the need for a proposal from the Commission, as it was considered a violation of national competence on certain issues and contrary to the principles of subsidiarity and proportionality. The process is still blocked by a lack of decision by the Council.

On 19 March 2021, the Commission presented its third report on the application of the Racial Equality Directive (Directive 2000/43/EC) and the Employment Equality Directive (Directive 2000/78/EC). The report highlights the challenges that still need to be overcome, but also identifies some possible ways to improve the application of the two directives. These include strengthening the role of equality bodies and supporting Member States in monitoring the application of directives.

For an exhaustive overview of the transposition status, country by country, we recommend reading the latest EC report https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/default/files/report_on_the_application_of_the_racial_equality_directive_and_the_employment_equality_directive_en.pdf.

In the video, the speech by Estonian MEP Yana Toom (Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe) at the plenary assembly of the European Parliament, on 15 September 2016, raises the relevance of the Employment Equality Directive in the area of the debate on the right of female workers to wear the Islamic headscarf.

In the video, the speech by Spanish MEP Javi López (Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament) at the plenary assembly of the European Parliament, on 10 February 2015, underlines the persistence of wage discrimination, highlighting how, to fill the gap between the wages received by men and women, the latter would have to work 84 more days a year.